By Gina Robinson.

Capoeira entered my subliminal consciousness as a teenager. I was watching TV when I saw two men performing kicks and acrobatics on a London rooftop. Barefoot, clad in red shirts and white trousers, their movements are in slow motion for maximum visual effect. Capoeira appeared again in a recent BBC Oneness ident, which features capoeiristas training at home during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Since becoming a capoeirista myself, I have realised that these fleeting images on television are highly exoticised performances styled for a British viewing audience. They rarely capture the musicality, community, respect, ritual and history that is part of this Afro-Brazilian tradition. Capoeira has become a popular practice worldwide and a national image of Brazil, along with samba and football. Outside of Brazil, it is easily idealised as an inclusive and exotic practice but without really acknowledging its origins, which are fraught with tension and conflict.

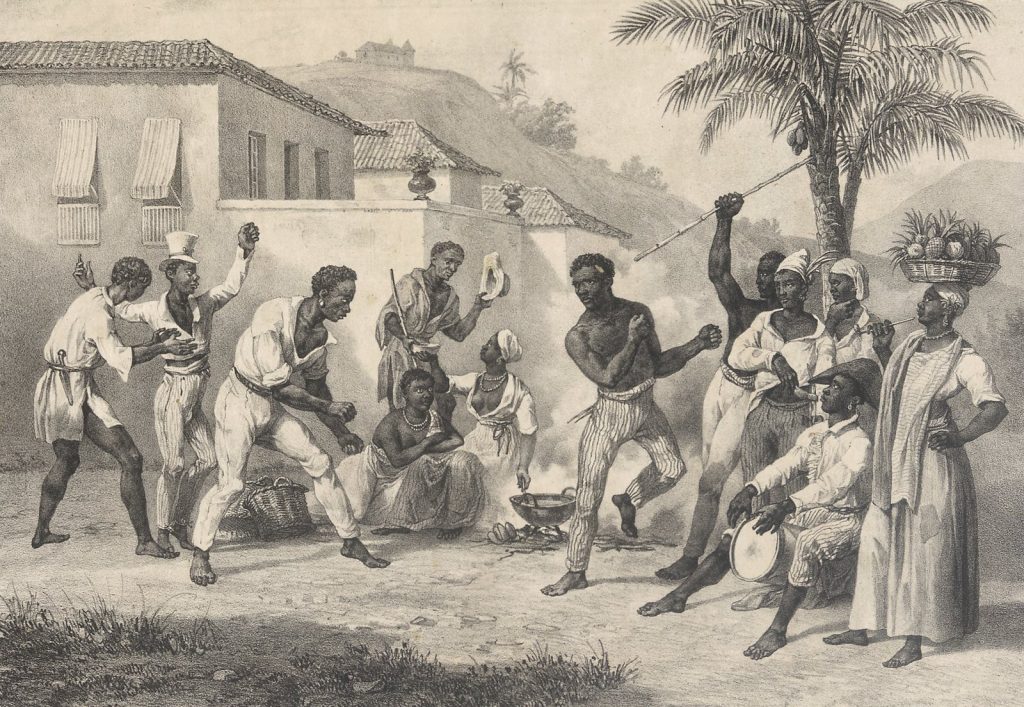

Capoeira is an embodied and musical art form, often described as a dance-fight game, which is thought to have emerged among enslaved African peoples in colonial Brazil. It was historically prohibited by Brazilian authorities who feared it to be an insurgent Black counterculture. Capoeira leaders began leaving Brazil to teach the art form abroad in the 1970s, and it is now practised in more than 160 countries around the world (UNESCO 2013). Searching ‘capoeira’ in Google today receives 21,300,000 results. However, due to the constant movement of practitioners between groups and countries and the absence of an official governing body, it is almost impossible to verify how many people currently practice capoeira.

In 2014, UNESCO granted capoeira the status of intangible cultural heritage, which raised its profile and recognised its importance in safeguarding Afro-Brazilian culture. Today, it has become an international marketing tool for Brazil and for disseminating the Portuguese language worldwide. Capoeira draws thousands of ‘capoeira pilgrims’ to the country to experience the art form in its native Brazil. Holiday and accommodation companies have jumped on the band wagon, providing package deals for Martial Arts tourism.

Capoeira today faces the challenge of embracing new economic opportunities as well as artistic interpretations and adaptations to its new national contexts. Competing myths and narratives have emerged as international practitioners seek and publish information about the practice. The growth of capoeira abroad has highlighted the need to respect its ancestry as a Black art of resistance and oppose attempts to professionalise it as a national sport.

The reference to capoeira’s African ancestry is upheld in the songs and narratives that are sung by Mestres – the highest-ranking position in the capoeira hierarchy, and whose authority and knowledge are revered by their community (but not necessarily by wider society). As capoeira has grown in popularity, some leaders and practitioners have resisted its internationalisation and commercialisation. This is because they fear that it dilutes and detracts from capoeira’s origins as an art of resistance. In the 1930s, Mestre Bimba was accused of ‘whitening’ capoeira when he began teaching middle class students. His capoeira Regional supposedly legitimised a ‘cleaner’ version of the art form when he opened the first official capoeira academy and introduced uniforms, belts and codified training regimes (Assunção 2005). More recently, Mestres in Brazil have resisted attempts to professionalise capoeira by introducing teaching permits that leaders must pay for to be officially recognised as a capoeira school. Mestre Paulão Kikongo (2019) claims this is yet another example of authorities wishing to control and profit from an Afro-Brazilian art form for political or commercial gain, after suppressing and condemning it as a barbaric and marginalised activity for centuries.

Capoeira actively promotes and preserves a rich Afro-Brazilian cultural heritage. However, this must be done without undermining the art form’s appeal to a diverse range of practitioners. Sociologist and capoeira Mestre Paula Cristina da Silva Barreto (2012) highlights the tensions between continuity and change. She claims that capoeira faces a ‘new scenario’ of accepting practitioners who are not part of the tradition, namely those who are not male, Brazilian or Black. For example, the recent growth in female leaders and practitioners has led to a surge in online discussions and academic research into sexism and social injustice, both in capoeira and in wider society (see the feminist capoeira research group Marias Felipas).

In UNESCO’s introductory video, the roda de capoeira (the physical circle in which games take place) is characterised by music, playfulness, creativity and challenging movements. But its most attractive quality appears to be its democratic inclusivity. The narrator tells us:

‘The dissemination of the roda de capoeira practice throughout the world is an example of the concrete possibility of respectful and harmonious coexistence between different ethnic groups, age groups and genders. It is a practice that promotes cultural diversity and combats racism and other forms of prejudice.’

These attitudes are often upheld by capoeiristas who view the art form as a positive force for change, and an alternative view of a more inclusive, respectful social order. Due to its international inclusivity, capoeira presents a useful vehicle for discussing the lived reality of identity and cultural politics.

We live in a world where differences between cultural practices are blurred due to mass migration. This has led to the hybrid fusion and adoption of different languages, beliefs and customs that are not necessarily part of our cultural heritage. For this reason, we need to think critically about popular images of traditional art forms that we see. As with any story, that of capoeira’s evolution has many sides, some of which are not always easy to digest, creating tensions that cannot be communicated effectively in a ten-second ident on TV.